Market Research Families Wealth Household Number of Kids Age

The economical well-being of adults ages xxx to 44 is influenced not simply past their own labor market place characteristics and those of whatsoever partners, merely as well past the nature of their households.

The measure of economical well-being used in this analysis already takes business relationship of differences in the size of the household, only the makeup of the household matters as well. The presence of children and other family members has important consequences for the amount of attempt adults devote to the labor market place and the number of earners in the household.

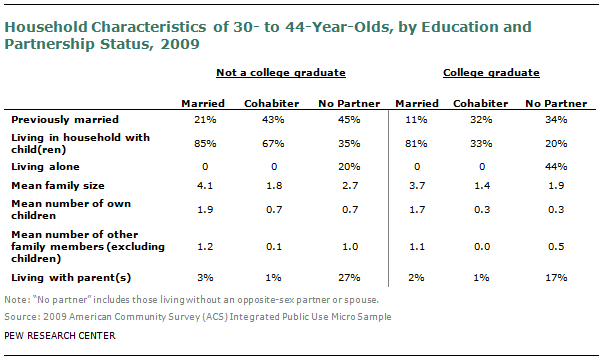

Married adults of all education levels are the most likely to have i or more children in the household. In 2009 married adults were about equally likely to have 1 or more children in the household, whether the adults were college-educated (81%) or not (85%).

There are sharp differences by educational attainment, yet, in the share of cohabiting couples with children in the household. But a tertiary of college-educated cohabiters alive with at least one child, compared with two-thirds of less-educated cohabiting adults.

Cohabiters without college degrees are more probable to alive with one or more than children for at to the lowest degree two reasons. Kickoff, they are more likely than college-educated cohabiters to take been married in the past. Among cohabiters without college degrees, 43% had been married in the by; among those with college degrees, 32% had been.

Second, there are notable differences in the child-begetting patterns of college-educated and less educated women. Less-educated women tend to deport children at younger ages, are more likely to have children while unmarried and are less likely to terminate their child-bearing years without having had children.

For case, amidst xxx- to 44-year-onetime women who gave nativity in the past twelvemonth, fewer than one-in-ten of college-educated women was single, according to data from the 2008 American Community Survey. The shares were notably higher—ranging from 21% to 34%—for women with some college instruction, a high school diploma or no high school diploma. Births to unmarried women include births to women who are cohabiting; they accounted for 2.two% of births to college-educated women ages 30 to 44 and 6% to 7% of births to women in that age group without college degrees (Dye, 2010).

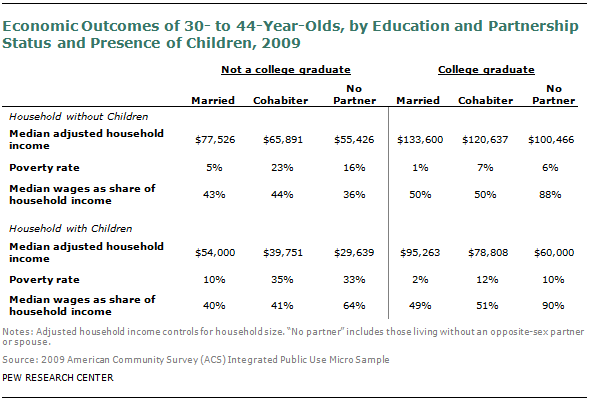

The presence of children in a household tends to have large economical ramifications. The table below reports the median adjusted household income of adults not residing with a child in the household versus residing in a household in which the adult is either a parent or the partner of a parent. Regardless of education or partnership condition, adults living with children are much less well-off than comparably educated adults who are not living with children. For example, consider college-educated cohabiting adults. Those with no children in the household have a median adjusted household income of $120,637. If one or both of the partners is a parent of a child in the household, their median adjusted household income is $78,808, nigh 35% lower than for a similar adult who is neither a parent nor the partner of a parent in the household.

The presence of children detracts from economical well-being because children crave fourth dimension and care; they likely lead to a reduction in hours devoted to paid piece of work on the part of the parent or the partner of the parent. They also increment household size, but the measure of median adapted household income accounts for differences in household size.

The presence of children detracts from economical well-being because children crave fourth dimension and care; they likely lead to a reduction in hours devoted to paid piece of work on the part of the parent or the partner of the parent. They also increment household size, but the measure of median adapted household income accounts for differences in household size.

Thus, a basic reason that cohabitation seems to economically do good college-educated adults but yields much lower economical dividends for less-educated adults is due to household composition. Amongst the college-educated, cohabitation is much less probable to involve living with children, and, peradventure as a issue, these cohabiters are likely to be members of dual-earner couples. Cohabitation amongst the less-educated two-thirds of the fourth dimension involves parenthood on the part of at least one of the cohabiters, and children tend to reduce measured economic well-being.

Another important household composition divergence involves the household members of adults non living with a spouse or partner. Once again, the nature of the household varies along educational lines. Among college-educated adults without a spouse or partner, 44% alive alone. The typical college-educated developed without a spouse or partner earns most of the household income—88% in the typical household, as shown in the table on page eleven.

By contrast, but 20% of less-educated adults lacking a spouse or partner live alone. Less-educated adults lacking a spouse or partner tend to alive in bigger families (2.vii family members versus i.nine family unit members), a difference only partly explained by their larger average number of children (0.7 children versus 0.3 children). Less-educated adults without a spouse or partner are more likely to alive with at least one of their parents. In part considering they often live with other adult family members, less-educated adults without a spouse or partner are not the only source of household income. The typical less-educated adult with no spouse or partner earns only 43% of the household income, one-half the share earned by the typical college-educated adult with no spouse or partner.

Given that less-educated adults without a spouse or partner often reside with other developed family unit members, cohabitation offers less of a potential economic windfall to them. By moving in with a partner, they may have the do good of that partner's income. Only by moving out of a household with other family members, they lose the economic resources those other family members contribute. Cohabitation does not necessarily produce cyberspace additional earners for the households of less educated adults every bit it does for higher-educated adults without a spouse or partner.

REFERENCES

Casper, Lynne Chiliad., and Philip N. Cohen. 2000. "How Does POSSLQ Measure Up? Historical Estimates of Cohabitation," Census, vol. 37, no. 2, May.

Dye, Jane Lawler. 2010. Fertility of American Women: 2008. November. Electric current Population Report P20-563. Washington, DC: U.Due south. Census Agency.

Goodwin, P.Y., W.D. Mosher, and A. Chandra. 2010. "Union and Cohabitation in the United states of america: A Statistical Portrait Based on Wheel 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth." February. Vital and Health Statistics, vol. 23, no. 28. Hyattsville, Medico: National Center for Health Statistics.

Fry, Richard, and D'Vera Cohn. 2010. Women, Men and the New Economics of Union. January. Washington, DC: Pew Inquiry Centre.

Garner, Thesia, Javier Ruiz-Castillo, and Mercedes Sastre. 2003. "The Influence of Demographics and Household-Specific Price Indices on Consumption-Based Inequality and Welfare: A Comparison of Spain and the United States," Southern Economical Journal, vol. 70, no. 1: 22-48.

Hamplova, Dana, and Celine Le Bourdais. 2009. "I pot or two pot strategies? Income pooling in married and single households in comparative perspective," Journal of Comparative Family Studies, vol. 40, June.

Kennedy, Sheela, and Larry Bumpass. 2008. "Cohabitation and Children'southward Living Arrangements: New Estimates from the United States," Demographic Inquiry, vol. xix, no. 47, September.

Kenney, Catherine T. 2006. "The Ability of the Bag: Allocative Systems and Inequality in Couple Households," Gender and Society, vol. twenty, no. iii, June.

Kreider, Rose M. 2010. Increase in Opposite-sexual activity Cohabiting Couples from 2009 to 2010 in the Annual Social and Economical Supplement (ASEC) to the Current Population Survey. September. Housing and Household Economical Statistics Division Working Paper. Washington, DC: U.Southward. Census Bureau.

National Center for Family & Marriage Research. 2010. Trends in Cohabitation: Twenty Years of Change, 1987-2008. October. NCFMR FP-10-07.

Nock, Steven L. 2005. "Marriage every bit a Public Consequence," The Future of Children, vol. 15, no. ii, Fall.

Short, Kathleen, Thesia Garner, David Johnson, and Patricia Doyle. Experimental Poverty Measures: 1990 to 1997, U.S. Demography Bureau, Current Population Reports, Consumer Income, P60-205, Washington, DC: U.South. Regime Printing Office (1999).

Simmons, Tavia, and Martin O'Connell. 2003. Married-Couple and Unmarried-Partner Households: 2000. U.Due south. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Special Report CENSR-five.

Smock, Pamela J., Wendy D. Manning and Meredith Porter. 2005. "Everything'due south There Except Money": How Money Shapes Decisions to Marry Among Cohabitors," Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 67, August.

Thomas, Adam, and Isabel Sawhill. 2005. "For Love and Money? The Impact of Family Structure on Family Income," The Time to come of Children, vol. 15, no. ii, Autumn.

stapletonexciation91.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/06/27/iv-the-households-and-demographics-of-30-to-44-year-olds/

0 Response to "Market Research Families Wealth Household Number of Kids Age"

Post a Comment